Jessica Hilltout welcomed me into her parents home, the place where she has a room of her own for those times when she’s not wandering. She made me some hot tea while I admired the proof-sheets of her photography on the walls, enjoying the depth she captures with her beloved Hasselblad; the camera that has become something of an extension of her own body.

I asked her about digital equipment versus the Hasselblad, and while she admits there is a certain temptation in the way a digital camera can more easily capture action and movement, shifting to digital would be about finding something as good as her Hasselblad.

We talked of her current project, an attempt at capturing the importance of football in African society. She explained ... ‘In Africa football is not a religion. But it’s everything a religion should be. And that is the aim of our project, to show how football holds African society together and how important it is to them. People live by it ... it’s a form of being able to dream of becoming a star, it gives them hope and it distracts them after a long day working the fields.

To capture this spirit,this very real energy without affecting it, Jessica works with a local person in each town or village she visits, finding someone who can act as a guide. It’s a method she developed while travelling alone in Madagascar. There she met local photographer Fidsoa, a kindred spirit who really ‘got’ her way of working and through working with him, she discovered the benefits of working with someone local and known.

The mention of Madagascar reminded me to ask Jessica about her previous project, titled Imperfection, and set in Madagascar. She explained that the idea had emerged out of a difficult period in her life, a period where she travelled alone for the first time and while finding it challenging, she learned to enjoy the way doors opened to her.

She explained the birth of the project, I found the word Imperfection ... it described so much of what I was trying to talk about. And so she teamed up with Fidsoa, the Madagascan, and together they journeyed through his world.

She went from Imperfection straight into the African football project, proposed to her by her father. She describes her father as a man who loves football and Africa; someone who has worked in advertising all his life but who, at heart, is a designer and an ideas person ...

She liked his idea.

Many photographers struggle with the difficulties of making their projects visible, of finding someone who wants to show them, and so photography becomes more about marketing, money, perseverance and luck. The luck of being in the right place at the right moment with the right person ... sometimes that is the miracle.

Jessica understood that this project would allow her the freedom to work her way and that there was also the possibility of commercial interest with the Football World Cup being hosted by South Africa in 2010. Quietly, she said, ‘I think that’s what might help this project rise from the dust and not get buried in drawers’.

She has some exquisite past works in those drawers.

They plan to launch the book during the Football World Cup ... the perfect location and time to introduce the world to the passion that is football in Africa. But more than that, it is the perfect forum in which to introduce the world to the passionate players who are stars in their own small corners of the continent.

Projects aside, the images that had first lured me into Jessica’s work those in her logbooks - as appear here on her website. I found them arresting ... which seemed to surprise her because they are very much a normal feature of her way of working. She began creating them in art college, where everyone had to develop their own way of logging their art studies.

She explained the logbook, ‘You can flick back and see how they are a subconscious way of forming your style. You find things in common. In fact, those four similar things I discovered in my college logbooks are still very much in how I work now’.

These days Jessica travels with a small digital camera, recording her journey, and a printer, which allows her to fill her logbook as she goes. This enables her to give the people she is photographing an idea of what she is seeking. It also enables her to map her own progress.

On the issues of trust and invisibility in countries not her own, she talked about the fact that she has lived and worked around the world and has accumulated experience in being accepted. Along the way, she has learned that sharing everything with people -water, food and space - shows them to know that her interest is genuine, that she really does want to know about them and their lives, that she is prepared to live as they live.

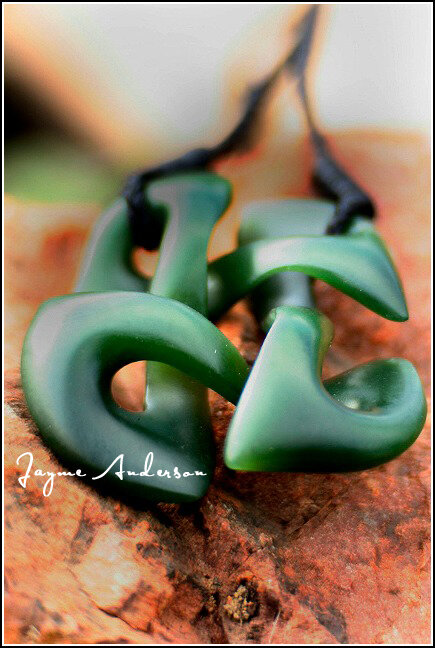

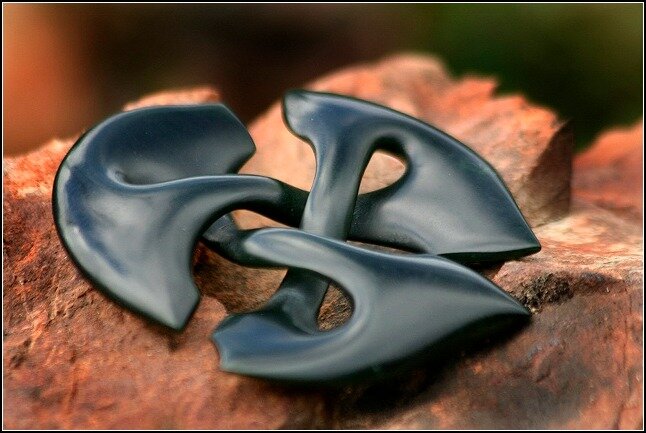

Tired boots and tired balls ... is the way the African people she met talked of their football equipment. Initially they had imagined she might be trying to show their poverty however Jessica was able to convince them that what she really wanted to capture was the fact that their ruined boots were only four months old and looked so shabby because they played everyday. That football is their passion and that this passion gives their boots a presence that is beyond branding by any company or the shine of new equipment ...

Boots can be a point of pride but simply because they have them. More importantly, they will play without boots, they will improvise with the ball too. Absolutely nothing will stop them from playing football.

And perhaps there was a small echo from Jessica’s imperfections project ... Little things are big. Less is more. Imperfection is Beautiful.

First published: December 8, 2011